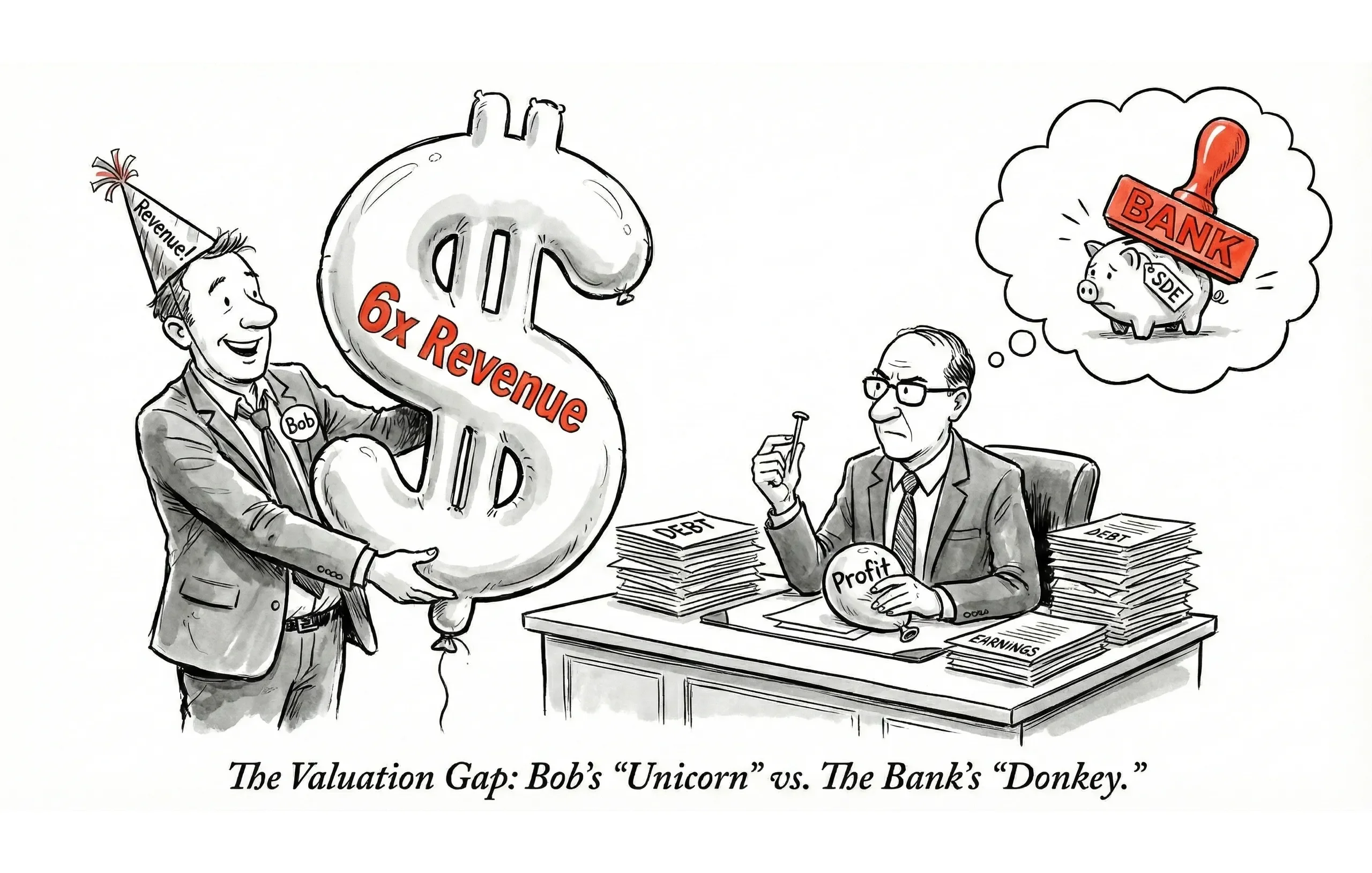

We’ve all had that meeting. You’re sitting down with a seller—let’s call him Bob—who owns a solid, consistent HVAC company. Bob slides a printout across the table. It’s a TechCrunch article about a software startup that just exited for 10x revenue.

"I think my business is worth at least 2x revenue," Bob says confidently.

You do the mental math. At $2M revenue and 15% margins, he’s asking for a 13x earnings multiple. You know the deal is dead before it even hits the market. Why? Because no lender will touch it, and no financial buyer can service the debt.

Understanding—and articulating—the difference between Revenue Multiples and Earnings Multiples is arguably the most critical conversation you will have to bridge the valuation gap, which kills roughly 26% of deals.

The Fundamental Difference: Vanity vs. Sanity

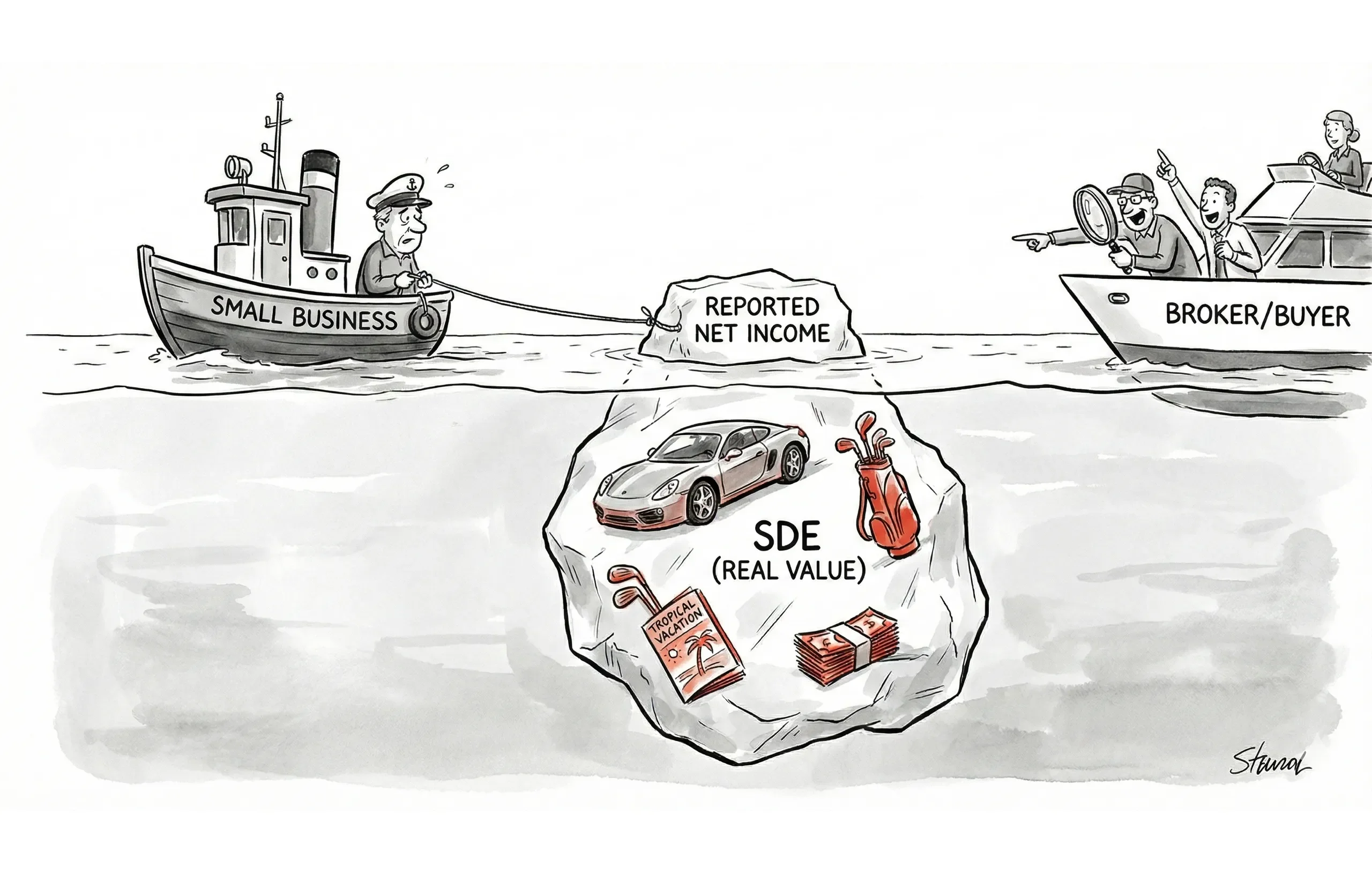

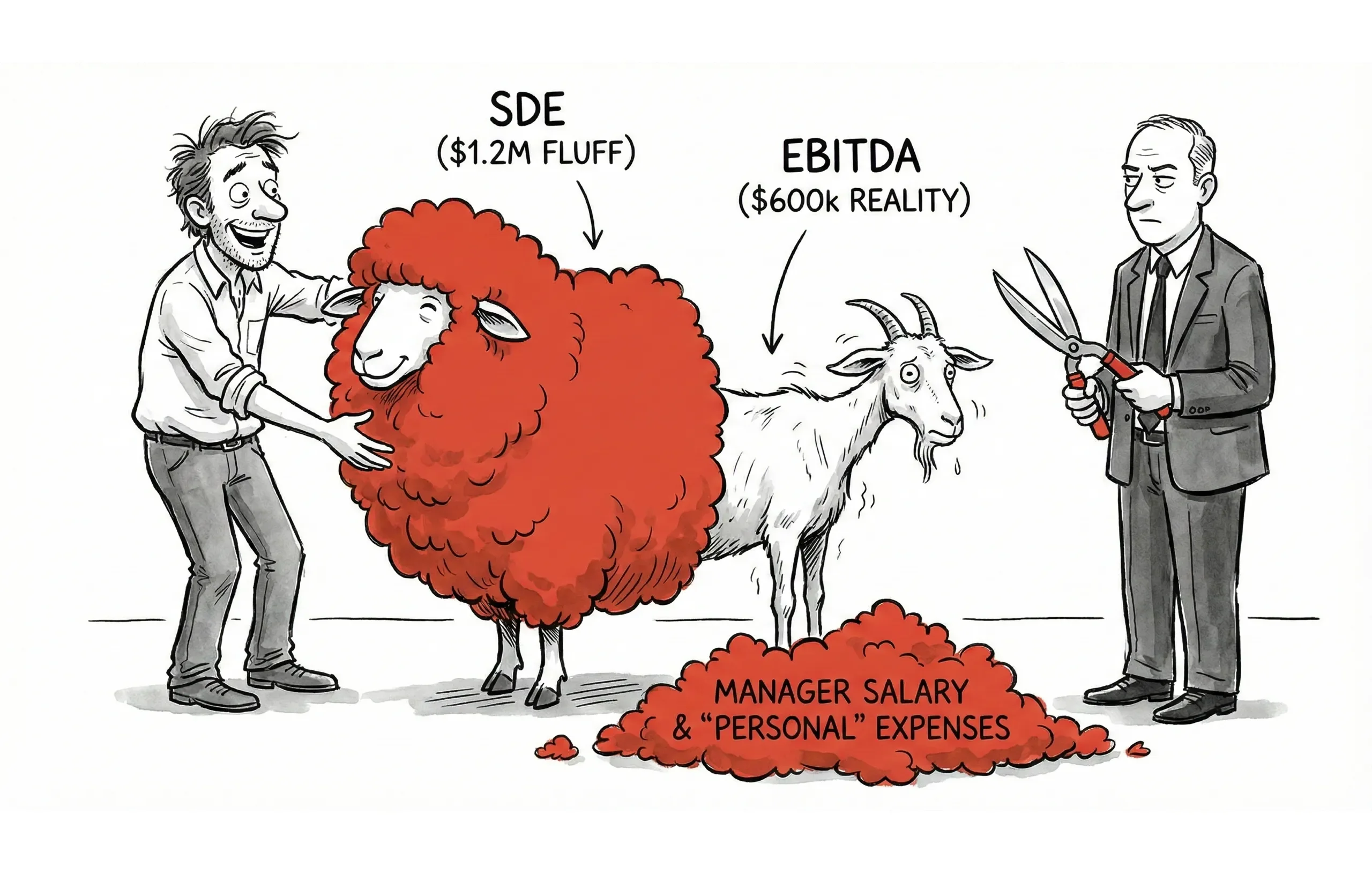

In the brokerage world, we often joke that "revenue is vanity, profit is sanity, and cash is king." But let's break down exactly what these metrics signal to a potential buyer.

Earnings Multiples (The Main Street Standard)

Value = Earnings (SDE or EBITDA) × Multiple

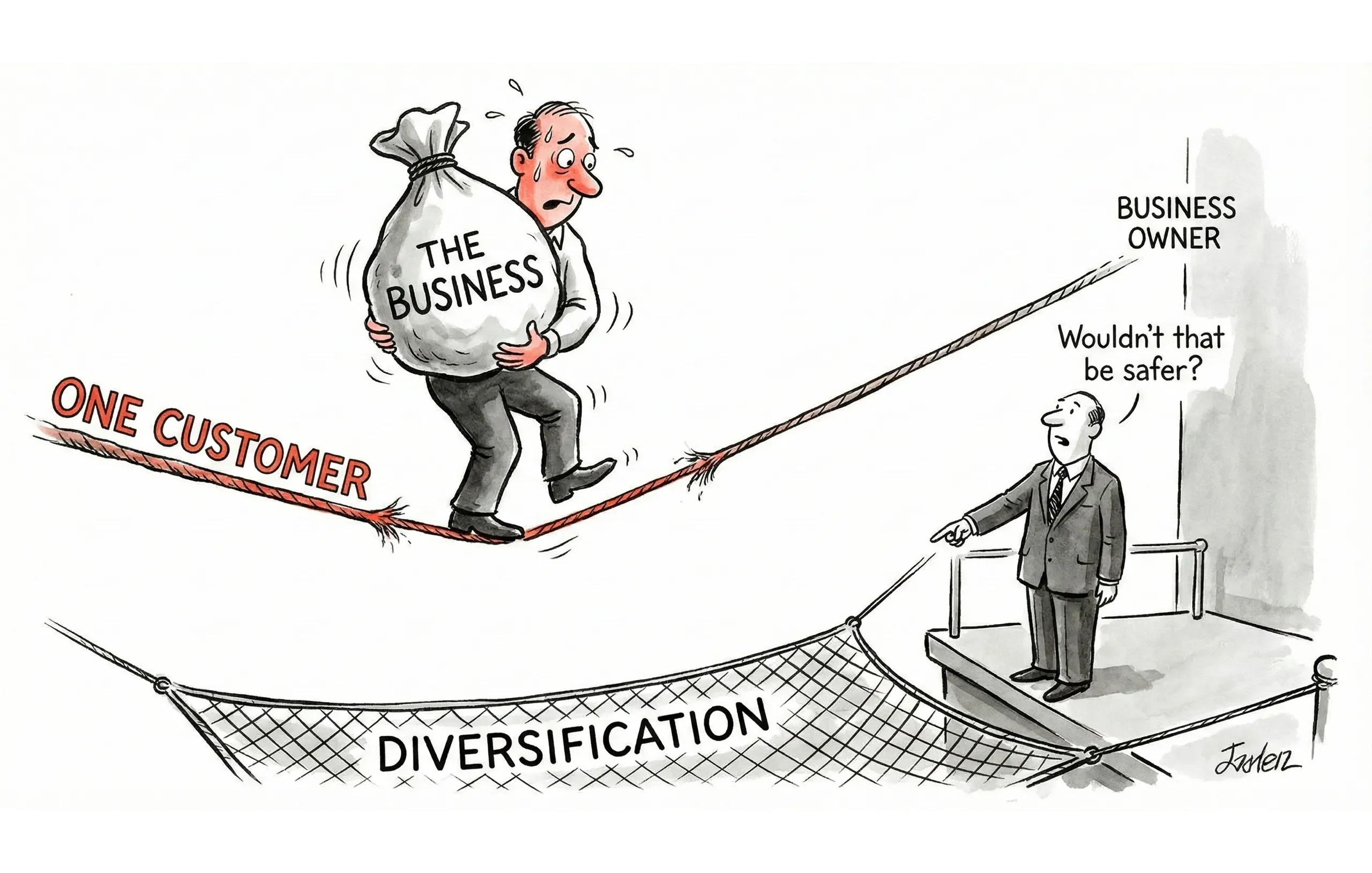

This is the "pay the bills" metric. It focuses on what the business actually puts in the owner's pocket after expenses. For 90% of the deals you broker—restaurants, auto shops, manufacturing, service firms—this is the only metric that matters because the buyer is buying a job and an income stream.

Revenue Multiples (The Growth Exception)

Value = Revenue × Multiple

This focuses entirely on top-line volume. It is reserved for businesses where the asset is the customer list or the market share, not the current cash flow. This usually applies to high-growth SaaS companies or strategic acquisitions where the buyer plans to strip out all costs anyway.

Why Earnings Multiples Dominate (The Banker's Reality)

You can find the "perfect" buyer, but if they need leverage, the bank holds the veto power. This is where the revenue multiple usually falls apart for Main Street deals.

The 1.25x DSCR Rule

SBA lenders typically require a Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) of at least 1.25x. This means for every $1 of loan payment, the business must generate $1.25 in available cash flow.

If a seller insists on a high revenue multiple that ignores profitability, the cash flow won't cover the debt.

The Data Backs This Up:According to the BizBuySell Insight Report (Q3 2024), the median service business sold for approximately 2.59x earnings, not revenue. If that same business sold on a revenue multiple, it typically traded at just 0.83x revenue.

Metric | Main Street Reality | Why? |

|---|---|---|

Profitability | Buyer needs income replacement | Buying a job vs. buying an asset |

Lending | Cash flow covers debt | Banks don't lend on "potential" |

Risk | SDE reflects proven history | Earnings show the model works |

The "Unicorns": When Revenue Multiples Actually Apply

While we spend most of our time managing expectations, there are times when a revenue multiple is the correct tool. If you are brokering a deal in the tech space or a distressed asset sale, keep these parameters in mind.

1. SaaS & Recurring Revenue

Investors pay for growth and "stickiness" here. According to SaaS Capital's 2024 data, private B2B SaaS companies have stabilized around a 6-7x ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) valuation range.

- Why? The buyer isn't looking for immediate SDE; they are looking for the "Rule of 40" (Growth % + Profit Margin % > 40).

2. Strategic Acquisitions

If a larger competitor buys a business solely to acquire its 5,000 active customers or to eliminate a competitor, they might pay 1x-2x revenue. They don't care about the seller's rent or payroll because they plan to absorb the customers into their own infrastructure.

3. Distressed / Turnaround

If a business is losing money (negative SDE), an earnings multiple is impossible. Here, you value the business based on a percentage of revenue (often 0.25x - 0.5x), arguing that a competent operator could extract a standard margin from that volume.

Revenue Multiple Ranges: A Cheat Sheet

When you do use revenue multiples, ensure your clients understand the drastic difference between a tech multiple and a traditional multiple.

Business Type | Typical Revenue Multiple | Context |

|---|---|---|

SaaS (B2B) | 3.0x - 7.0x ARR | Driven by retention & growth rates |

E-commerce | 0.5x - 2.0x | Higher for proprietary brands, lower for dropshipping |

Prof. Services | 0.8x - 1.2x | Accounting/Legal (often sold as % of billings) |

Main Street Service | 0.4x - 0.8x | HVAC, Plumbing, Landscaping |

Restaurants | 0.25x - 0.4x | High risk, low margin |

The "Napkin Math" Reality Check

The best way to handle a seller fixated on revenue multiples is the Conversion Test.

Let's say a seller wants 1.5x Revenue for their $1M manufacturing business.

- Ask Price: $1.5M

- Actual SDE Margin: 15% ($150,000)

To justify a $1.5M price tag on $150k earnings, the buyer would be paying a 10x SDE multiple.

- Market Reality: Manufacturing businesses currently trade closer to 3-4x earnings.

- Result: The deal is overpriced by nearly 200%.

When to Investigate Further:If the revenue and earnings methods yield wildly different numbers, check the P&L for "add-backs." Is the margin artificially low because the owner is running personal expenses through the business? If you normalize the SDE and the multiple aligns, the revenue method might just be a coincidence.

Talking to the Seller: The Pivot

When a seller pushes a revenue multiple, don't just say "no." Pivot the conversation to borrowability.

Try this script:

"Bob, I completely understand why you're looking at that 2x revenue figure. In the venture capital world, that's standard. But for a business like yours, the buyer pool is using SBA leverage. The bank is going to stress-test the deal at a 1.25 debt coverage ratio. If we price it at a revenue multiple, the bank kills the loan, and we lose 90% of our buyers. Let's price it on SDE so we can actually get you to the closing table with a check in hand."

By shifting the blame to the "bank's requirements," you move from being the adversary to the advisor.